#ChileDespertó: an Explanation of What is Going on in Chile

On October 7 2019, Chilean secondary students decided to 'evade' public transport fees in response to a proposed fare hike (of roughly 30p). Within just a few days, the metro protests spilled out into the streets. They have not stopped since, nor does it feel as though they will.

There have been all sorts of ways that people have taken action: Well over a million people took part in the biggest demonstration in Chile's history. Meanwhile, countless metro stations, supermarkets and shops have been looted and burnt, as well as local cacelorazos taking place in barrios (neighbourhoods).

[*A cacelorazo is a popular form of protest throughout Latin America. People come together with pots and pans to protest in a noisy fashion and demand attention.]

The response from the state has been extremely heavy handed and militaristic. By October 18, President Piñera declared a state of emergency. This brought the military out into the streets, installed a curfew and declared it illegal for people to 'gather'. The state of emergency lasted ten days. During this time, the President reshuffled his cabinet but refused the calls for his own resignation. Although the government has since said that the metro price will not rise, and has offered raises to the minimum wage, the protests are not abating.

Friday night protests in Chile.

At the time of writing, there have been: close to 30,000 thousand arrests; hundreds wounded by pellet guns; over 200 who have lost at least one eye from pellet guns and tear gas canister wounds; over 75 allegations of rape by police officers; and over 20 dead.

Everyday at Plaza de la Dignidad protesters meet to fight the police for control of the square. Everyday there are even more local barrio assemblies. Everyday more graffiti – artistic and not so – goes up. It may sound strange that a fare hike on the metro could lead to all of this. But one cannot understand the current state in Chile as something singular; something that occurred in a vacuum. In order to understand what is happening in Chile today, one needs to look at the Chile of yesterday.

“It's not 30 pesos, it's thirty years”: Chile’s Heritage of Dictatorship

In fact, one has to go back to September 11, 1973: the day Salvador Allende, the democratically elected left-wing President of Chile, was ousted in a bloody coup. Santiago awoke to their presidential palace, La Moneda, being bombed. By the end of the day Allende was dead. He was replaced by General Agusto Pinochet. Pinochet installed a military junta with him at its head. Pinochet's dictatorship in Chile lasted for 17 years.

The period under Pinochet was one of brutality, suppression of human rights and the installation of neoliberalism as the country’s political ideology. This led to the persecution of leftists, socialists and, realistically, any critics of the regime. The result was the execution of up to 3,000 people, the imprisonment of up to 80,000 people, the torture of an uncountable number, and the forced disappearances of over 3,000.

In 1988 a plebiscite was held on whether the Chilean people wanted Pinochet to carry on with his mandate. The 'No' campaign won. This result meant that the country would enter a transition period for the next two years, after which they would hold democratic elections. Yet, the plebiscite didn't point to the total reversal of everything that had occurred under Pinochet…

The dictatorial period wasn't just about anti-communist enforcement. In large part, it was about imposing neoliberalism. Guided by the Chicago Boys – right-wing Chilean economists from the 1970s and 80s, so named for studying under Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger at the University of Chicago – Chile was the world’s first experiment in neoliberalism. Almost everything in the country was privatised, including water. Within Chile, every source from which drinking water comes (rivers, lakes, glaciers, etc) is privately owned.

Given that the end of Pinochet came in the form of a referendum, the neoliberalisation of the country remained intact. In fact, as mentioned, Pinochet was allowed to finish his time in power; he didn't leave until 1990. During these last two years, he carried on the neoliberal project bringing in laws up until the last day of his time in power. This was seen as the 'Chilean miracle’: a country based on free market economics, putting business and profit before the people. But this constant neoliberal growth has been occurring, since 1973 to this very day, in front of a smoke screen of injustices.

The plebiscite of 1988 promised Chile happiness. A jingle used as part of the campaign (on which the film No is based) has at its centre the slogan “Chile, la alegria ya viene”: Chile, happiness is coming.

However, the current Chilean slogan suggests otherwise. “It's not 30 pesos it's 30 years” references the fact that the transition of power saw little change in the post-dictatorship era. Happiness still hasn't come…

“Neoliberalism was born in Chile and here it will die”: The Fight for a New Norm

Three years ago I studied for my year abroad here in Santiago. Back then I felt as though something had to give. Every week there were demonstrations calling for change from different sectors of the country. For my last two months of studying, 90% of universities in Santiago were on strike (both students and teachers) and 65% of them were in occupation. Many secondary schools also declared a student strike and occupations.

Protesters young and old are fighting together for a new Chile.

Chile is the most unequal country in the “developed” world, where strikes, protests and occupations have become the norm. A normality that, frankly speaking, Chileans have had enough of. I felt as though things just couldn't carry on as they were, everything was just far too tense. The metro fare hike was just that: a forced break from the everyday – it was the proverbial last straw.

The demands on the Chilean streets in 2019 are wide-ranging. Each expression of anger and demand for change is different from the next but cannot, at the same time, be separated. Each is an image and vision of a new normality.

The government has estimated that over the last 50 days about 21% of Chilean society has, in one way or another, participated in the protests. For reference, in the UK, that would be the same as 13 million people turning out, getting active and participating.

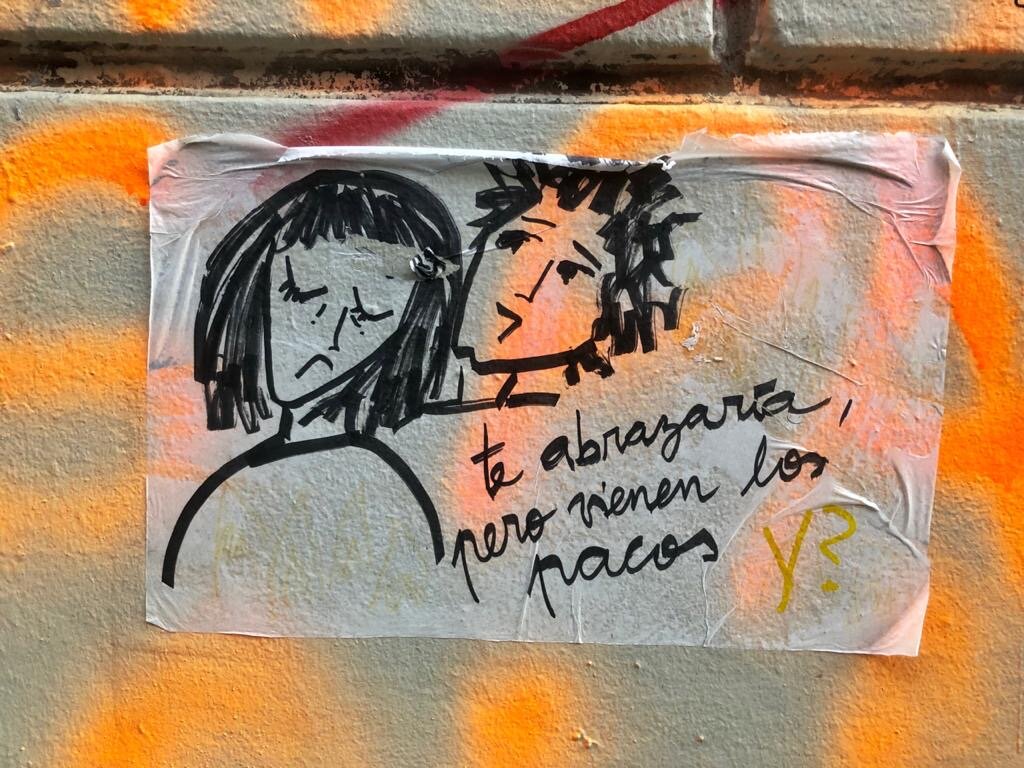

Santiago’s Graffiti: “I would hug you but the police are coming”

I have found that one of the best ways to understand the different demands is simply to tour the graffiti-lined streets of Santiago. From simple tags of 'No + AFP' – against the pension scheme brought in by the current president's brother during the dictatorship – to works of art against police and military violence, the demands are many. Students are fighting against the educational system. Mapuches and other indigenous groups are fighting for autonomy and recognition. Almost every household is fighting against the system of privatised electricity, water and gas... the list goes on and on.

When touring Santiago, you are likely to run into re-creations of the now-global feminist performance: ‘Un Violador en tu Camino' (A Rapist in your Path). This unified chant began in the Chilean town of Valparaiso and has since been recreated throughout Chile and in 17 other countries.

‘Un Violador' plays off a well-known hymn that celebrates the Chilean police officers’ “protection” of the nation’s innocent girls. This feminist uprising speaks to the fact that Chile has a high rate of sexual harassment, rape and femicides, including many perpetrated by the police themselves. During this period of protests alone, two videos have circulated of the police attempting to arrest girls, under the age of 16, by first pulling off their tops. Many have denounced their treatment in police custody, with a high count of allegations of gender violence including rape. The police are finally being named and shamed.

Everyday in Santiago there is something new to get involved in. Everyday the police use absurd levels of repression to try to quell these events. Demonstrators are faced with tank-like water cannons. Tear gas is pumped out to such a level that Human Rights Watch have said could be lethal. But it's not enough. The people are fighting for a new normality, a new system, a new Chile. And it feels as though nothing can stop them.

Keep up with Tamara’s first-hand accounts from Santiago on her Instagram. And follow the latest action on the ground across Chile thanks to Frente Fotográfico (who supplied the title image, via Instagram).

See the global female uprising in action here, courtesy of Guardian News: