Directing: Can Diversity Change the Film Industry?

by Marion Herve

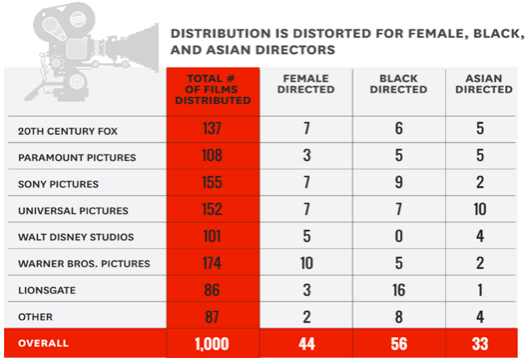

Inclusion in the Director’s Chair is a report published in 2017 by the University of South California which produced data about the directors of 1,000 films released between 2007 and 2017. The aim was to highlight the inequalities in gender and race when it comes to being a film director in Hollywood. Although these inequalities were not unknown before, the merit of this report is that it highlights the depths of imbalance.

It is easy to justify the need for more inclusion from a political point of view: discrimination is wrong, period. Yet, I have often been asked if I thought that inclusion would actually bring anything positive to the film industry. After all, do we need an nth chick flick or another Dr Dolittle? Overlooking the misogyny, racism or homophobia surrounding such remarks, they do raise an interesting question: are films made by female or minority filmmakers any different from the ones made by white heterosexual men?

Looking at recently released films directed by women and/or people of colour, one thing immediately springs to mind: the cast tends to be a lot more diverse. I do not mean that films made by black people will tend to portray mainly black people, and films made by women portray mainly women, etc. This does happen, but there is more to it: we can often see an altogether more diverse cast within one film. It seems that when directing a film, women or people from minorities seem to be more consciously aware of the discrimination that others might be victim to and, as such, they try to contribute to the resolution of discrimination in general, not just the prejudice they personally face. For example, in A Wrinkle in Time, Ava Duvernay presents a diverse cast, dominated by black women but also featuring Mindy Kaling, an American actress of Indian ethnicity, and the talented Deric McCabe, who is of Filipino origin. Similarly, in Black Panther, Ryan Coogler includes a multitude of plot-relevant and interesting female characters; and in You Were Never Really Here, directed by Lynne Ramsay, we can observe a great diversity of race and gender among the extras.

More diverse film directors are also helping to break clichés. On top of being underrepresented, women and people from minorities tend to see their characters’ behaviour defined by stereotypes. For example, black women will tend to be characters defined by negative identities, often portraying a limited range of characters such as the slave/servant; see Octavia Spencer in The Help. Generally speaking, people of colour are often victim to what is called the ‘Magical Negro effect’, i.e. a black character with some sort of power and/or wisdom whose role is limited to helping the white protagonist. This includes, but is not limited to, Morgan Freeman in Bruce Almighty, Morgan Freeman in Now You See Me 2 and Morgan Freeman in Batman Begins. Similarly, characters who are identified as a potential member of the LGBTQ+ community will tend to be defined by their sexual identity, or at least see it play an important part in the way they are portrayed, e.g. Damian in Mean Girls.

Thankfully, there seems to be a growing number of films which benefit from what I refer to as the ‘Star Wars Phenomenon’, especially in films directed by women and/or minorities. These are films portraying a somewhat diverse cast and in which the race, gender and/or sexual orientation of the characters is purely anecdotical and does not define the whole, if any, of a character’s personality and actions. For example, in the three latest Star Wars films, the main protagonists were women (i.e. Rey and Jyn), but the films are directed in such a way that their characters are in no way more feminine than masculine. It is as if the script was written to include characters whose genders were undetermined, so actors were cast for the roles who delivered the performances most fitted to the characters’ personalities/descriptions. They are all just people.

We can see something similar in Love, Simon, a film directed by Greg Berlanti (whose own sexuality is presumed to dictate his films). Yes, it is a story of a male homosexual teenager trying to navigate through high school; but his sexual orientation is not his defining personality trait. The film questions what it means to be gay and whether or not coming out should mean that Simon suddenly has to start to act in line with society’s assumptions. Ultimately, the take away message is this: sexual orientation does NOT define the person you are.

Finally, it can also be said that diversity among film directors leads to diversity of social experiences and so, diversity of stories and subject matters. Indeed, it is undeniable that the way society and people treat us varies depending on where we live, our social background, the colour of our skin, our sexual orientation, our gender, etc. So, it often seems ridiculous, and even offensive, that stories we may relate to are told by people who have no idea what it is to live through them. For instance, there is no shortage of films targeting high school girls which are directed by men (e.g. She’s The Man, The Princess Diaries or The Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants). No offence gentlemen, but what do you know about being a teenage girl in the noughties? This is why I would rather see films more like Lady Bird, directed by Greta Gerwig which depicts the life of a teenage girl, with ungendered character traits: she chooses to re-baptise herself and portrays gender neutral teenage stubbornness. Lady Bird also presents certain experiences of life that are linked to social background (i.e. dealing with wealth inequalities at school) or gender (the way sex was pictured and talked about reminded me, among other things, of the book Girls and Sex by Peggy Orenstein, an in-depth study of the sexuality of girls and young women in the U.S.).

Even worse than directors creating films about experiences they cannot fully understand, is that certain life experiences might be altogether ignored. For example, some might think that the underlying denunciation of racism and inequalities that black communities suffer from do not really fit in action and horror films. But Black Panther and Get Out both include these themes in a coherent way because, for the people who made these films, it is part of their lives even if we do not want to face it.

I am not saying that white male directors necessarily get it wrong. In Annihilation, director Alex Garland managed to portray the story of believable female characters and the overall cast is very diverse. Nor am I saying that I never again want to see stories of princesses rescued by princes, black characters supporting a white hero or effeminate homosexual characters. The problem is that these characters and stories are dominant, creating a biased vision of the world in which not everyone can feel they are being represented and that is an issue. We need more diverse directors to create a more diverse film industry. It can only lead to more creativity: wouldn’t that be amazing?

Image sourced via Flickr.

Marion is a French feminist and film buff. Read more by Marion on Harpy.